Please introduce yourself, tell us a little bit about where in the region you are based, and share some of the major ideas and themes you engage with in your practice.

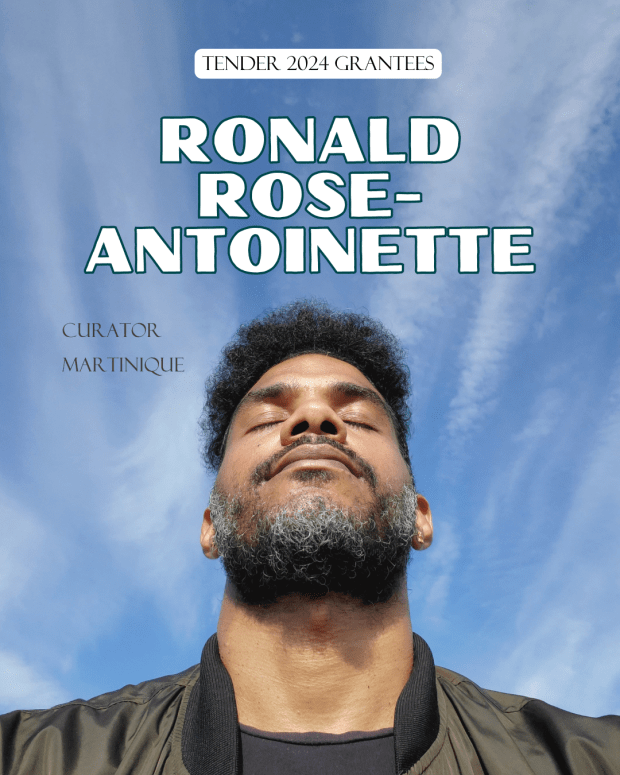

I am a Martinican scholar and independent curator interested in advancing creative experiments in anticolonial and antidisciplinary practice. I am based in Martinique.

My scholarship and curatorial practice are embedded in portals, doors, passageways, holes, cuts, thresholds. While I am being intellectually and aesthetically invested in the ways through, paths, modes of transmission, of ecstasy even, I am also interested in what grows on the edges, how porous or leaky the frontiers can be, how communities–human and nonhuman–flourish at the border, all borders, strain against the limits imposed upon them, how aesthetic life is imagined collectively on the move, how we get ourselves across in difference.

I am less interested in speculating on a self-secluded utopian community than in exploring how art practices give us access to an alternative form of collective life, a “we” that is more subjunctive than subjective, that remains in a state of re-enchantment, re-conditioning through the generative, creative and critical relations of its differences.

I situate my work in the context of a larger effort to think or rub aesthetics against power, structures of dominance, systems of thought, doctrines, theological, metaphysical, and philosophical, that continue to make genocides and ecocides possible.

Can you speak about the artist residency ‘in the shade’ that you developed and the ways in which it has nurtured conversations about collective care, gender and sexuality, diasporic homesickness and the sense of being a stranger in one’s so-called native environment? What other challenges or unexpected experiences have you faced in the establishment of a regional residency programme?

Conversations about collective care, play, unguarded susceptibility to nature, camouflage, senses of dis/placement and dis/possession, were nurtured through a certain kind of approach to hospitality, to providing breath, rest, and shelter.

It was important to me that the artists that I invited came during carnival to experience procession, release, exodus, to immerse themselves in the priority and futurity of what is colloquially known as “vidé”, an extravagant impediment to security and containment.

The program included a series of activities such as an evening of music and dance at Maison du Bèlè where they learned about bèlè as an act of equivocation, liminality, and contradiction, contributing to an open-ended chorus of shady performances, gestures of trickery and misdirection audible across Afrodiasporic communities; an afternoon at a pottery workshop during which they embraced an elemental comportment to world and reality through clay and water; and an evening with Mr. Diop, a healer and hougan, oriented toward an appreciation of the complexities held in, as, and by water in the constellatory reverie of Black mysticism.

To help facilitate these activities, I reached out to several local institutions and organizations but received no financial support, and sometimes simply no responses. Generally speaking, many of the people I contacted seemed reluctant to contribute or, quite frankly, to listen. I submitted a grant application through the French Ministry of Culture back in December and have not heard from it since. My savings combined with the support of Fresh Milk, and the purchase of all the plane tickets by 2 of the participants, made this first residency possible.

In addition to initiatives like TENDER, what other kinds of support or programming geared towards the needs of contemporary creative practitioners would you like to see implemented in the Caribbean?

I simply wish that people in my own country showed at least some sympathy toward a project like this, or at least an inclination toward listening. Thank you Fresh Milk for your trust and generous support.