Sonia Farmer writes about her third week in residence at Fresh Milk. Continuing her erasure poetry project using the text ‘A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbadoes’ by Richard Ligon while conducting her own exploration of the island, she contemplates the loaded act of ‘discovery’ and the implications it carries. She also shares the outcome of the challenging but successful third week of her book-binding workshop ‘The Art of the Book‘, which saw the students begin to create their own hardcover notebooks and leather journals. Read more here:

Lives in and out of the studio are converging in interesting ways given my chosen project. I’m still working my way through an erasure of A True and Exact History of the Island of Barbadoes by Richard Ligon, but also discovering more of the island myself. The week began with thrilling visits to Harrison’s Cave, Hunte’s Gardens, and Bathsheba, all self navigated with a car rental rather than a pre-arranged tour. We became dreadfully lost on the way to the cave, got soaked in one of those short-lived island downpours in the gardens, and found our recommended lunch place closed due to construction with dangerously low blood sugar levels—but we could say we had a pretty fantastic adventure. Similarly, I’m reconnecting with a Bahamian friend who lives here in Barbados. When she asks what I would like to do around the island, I answer, “Anything.” I’m hungry to see and do it all.

These moments bring out the romantic in me, even though I know all too well the often-frustrating realities of island living and rolling stone travel. But just as I felt during our Week One island tour, exploring a new space is a thing of wonder and an entirely individual experience, something that I am trying to honor and witness in my personal journey as well as my creative practice. I want to be an explorer, not only of physical space, but emotional space too—to study how we meet new experiences with both head and heart.

Is discovery the endgame? Discovery is a problematic word for me, but one that I have been turning over in my head as I think about what it means to write “a true and exact history” of anything: the weighty privilege of it, the naiveté, the narcissism, the violence, all inherent in that word as we have learned it, especially in the Caribbean. We all know the story: In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue. Good for him. Not so great for others. Because we know that no place can be “discovered” that has already existed in the minds and hearts of others. What maybe can be discovered is something entirely individual and emotional, found on an inward journey while on the outward journey, and that discovery is completely personal. The “true and exact history” of the world as we have learned it is a myth. I don’t think discovery is an endgame here. Exploration and deconstruction, perhaps.

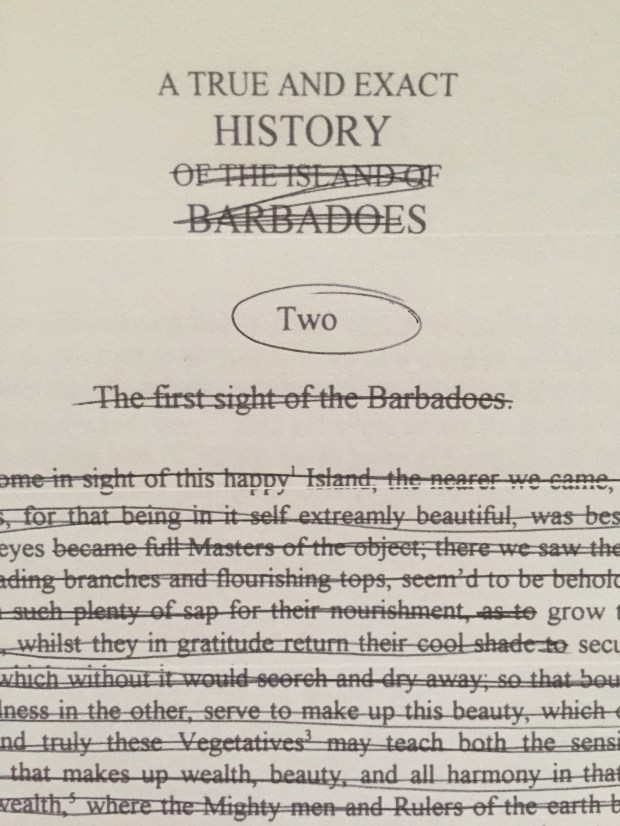

Because when I revisit this historical text by Richard Ligon, a man who, by his privilege, has found a spot in this island’s history, I am interested in deconstructing and reconstructing through the act of exploration. I’m drawn to finding a new narrative within the existing narrative, one that touches upon emotional landscape. And one that honors the fact that if I had approached the text on any other given year, or day, or hour, I could pick up on a completely different set of words and perspective. And that would be true for any other person I hand the text over to.

So I don’t want to think about the history of discovery, I want to think about the discovery of history. I want to think about the act of exploring. I want to explore what we carry and what we choose to include vs. what we overlook and what we choose to leave out. I want to think about the fragility of the moment in the process of choosing one story over the other, and why we are drawn to that. I want to think about making space and leaving room. I want to think about the stories we tell ourselves when we only have one version of history to work from, and how we can still find power and wonder and self-discovery in that. Or not. I have my own set of privileges guiding my through the process behind this project. So overall, I want to keep it personal, because there is no true and exact history.

Meanwhile, setting aside the 24 hours I thought I was coming down with a flu but somehow gained strength from a fantastically indulgent meal at Chefette, my students crushed week three of our workshop when they sewed their first multi-signature text blocks to create two different blank notebooks. One will be an exposed-stitch hardcover, while the other will be cased into leather for a travel-notebook. As usual, I was completely too ambitious within my given time-frame, even though we extended the class by an hour. Luckily, week 4 is a catch-up class as well as a fun final class, so we will case in our notebooks, revisit a group project, and then make some quick fun book structures. Also luckily, they all had a blast even though I know it was a very challenging class and I couldn’t split myself into three people to assist everyone, but they passed with flying colors. I’m so proud of them!